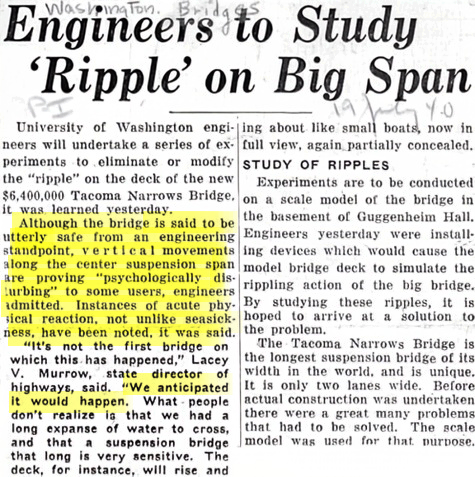

I love this article, from the Seattle PI, in July 1940, on some “unusual” behavior on the just-completed Tacoma Narrows bridge — the same bridge which collapsed spectacularly 4 months later. I particularly enjoy this part:

Although the bridge is said to be utterly safe from an engineering standpoint, vertical movements along the center suspension span are proving “psychologically disturbing” to some users, the engineers admitted … “we anticipated it would happen.”

Of course, the engineers and scientists were wrong — catastrophically so— and assurances based on the absolute certainty of their science and dismissal of terrified drivers as ’emotionally disturbed’ proved wildly and humorously laughable in retrospect.

Some things, it seems, never change: scientists never have doubts — and those who question their inerrant wisdom must be ‘mentally disturbed.’

In a previous essay on the universe’s origin, I took to task an astronomer who, while presenting a most interesting but rather far-fetched (to my mind) explanation of the universe’s origin. He also took the opportunity to ridicule as foolish and ignorant anyone who conversely postulates a divine Creator. He then took me to task for needing to rely on “religious stories” to make myself feel better:

Me: “I have instead been transformed by a personal encounter and relationship with a Being far vaster than our paltry imagination and feeble intellects can begin to grasp.”

Scientist: “There’s no evidence for this encounter at all.

“To consider the imagination ‘paltry’ is to have little understanding of how your imagined ‘relationship’ … is different from a perceived real. This difference may well be so imperceptible to the believer that a psychologist might consider this to be a form of psychosis.

“Your understanding of the transcendent is also an uneducated one … I think you need to spend time with real scientists who gaze at wondrous things every day.

Aahh, the humility of our scientist-priests …

As my wont, I decided to contest his modest assertions. To wit: concerning my personal transformative experience and personal encounter with God, my agnostic antagonist sought to educate me as follows:

Scientist: There is no evidence for this encounter at all.

This is a rather presumptuous statement, is it not? — yet hardly a surprising one. Our scholarly skeptic knows nothing of my genetics, naught of the blessings and banes of my family of origin, nothing of my life experiences in childhood or adulthood. He does not know my thoughts, experiences, successes, or failures, nor the irrefutable, transformative effect of the power of spiritual relationships in my life. Yet he, presumably a secular scientist steeped in evidence-based knowledge, blithely dismisses all such experiences and evidence and, without even a hint of irony, assures me that there is “no evidence for this encounter at all.”

What is evident, however, is that evidence has nothing whatsoever to do with his assertion: it is, pure and simple, a declaration of his worldview or, more accurately, his religion.

But religion? How can secular materialism/atheism be a religion, since they don’t believe in God?

We generally think of religion within the framework of the great monotheistic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, one God, albeit with different dogmas. But other religions abound: polytheism, animism, nature worship, ancestor worship, etc. They all have absolutes they embrace, i.e., dogmas, and a central source for these truths held without ambivalence, held in the highest regard. So what is the deity, the god of secular materialism?

Knowledge.

Or, more accurately, Man and his knowledge — in particular, their own.

The secularist’s creed – if you will, his dogma – is this: there is no God, nor any possibility of God. Man and his knowledge are the pinnacle of all existence, the answer to every question. This is their a priori position, and all evidence or suggestion to the contrary, must be dismissed, ridiculed, or ignored, and is indeed heretical. The scientific method has nothing to do with this conclusion; there is no postulate to test, no experiments to evaluate, no revision of theory based on experimental outcome, no possibility of an answer other than that already predetermined. This is not science — it is theology — and religion in its worst form: blind faith manifested by absolute certainty, intolerance, condescension, judgmental, unshaken by any evidence but that of their received or derived comprehension. The very thing I stand accused of — addiction to absolute certainty — is his own most significant blind spot: he is tenacious in his self-assurance that God does not exist. All other facts, experiences, and contrary evidence from my life, or anyone else’s with similar experience, must be bent, folded, and mutilated into this materialistic worldview. Chesterton once observed, “Only madmen and materialists have no doubts.”

Scientist: “To consider the imagination ‘paltry’ is to have little understanding of how your imagined “relationship” is different from a perceived real. This difference … may be so imperceptible to the believer that a psychologist might consider this a form of psychosis.

At last, the diagnosis I have long suspected: psychosis — that’s the answer: I’m mentally ill! Well, I can assure you I am quite sane — even my psychiatrist friends agree. As a physician, I know something about psychosis: its clinical manifestation and symptoms are well-understood, having seen many patients suffering from this mental health disorder. But for the secular materialist, such standards of diagnosis are moot; from the proclamations of their psychic soothsayers – psychology and psychiatry – function as both savior and sword. When your secular scientific theories fail to explain human behavior, evil, or religious experience, it’s time to send in the clowns, wrapping your befuddlement and disdain in psychological terms like “psychosis.”

That which scientists cannot explain about human behavior, they delegate to the psychologists. But psychology and psychiatry have another significant utility for the atheist: a weapon to attack and neutralize those who reject their orthodoxy. It is no accident that psychiatry became a potent weapon in the hands of secular totalitarian states such as the Soviet Union. If you are not loyal and enthusiastic about the State and the Party, you may well find yourself in a mental hospital, where you will be “treated” until you see the light. A similar fate awaits you for religious impulses as well. What you cannot explain, you must explain away; what you cannot explain away, you must persecute. Mental health services in the gulags were freely available for all who disagreed.

I greatly respect mental health professionals, but they make far better physicians than metaphysicians. When ordained to their postmodern priesthood, tasked with diagnosing and healing man’s soul and spirit while dismissing their reality and centrality, they look quite as foolish as engineers dismissing bridge ripples.

Scientist: “Your understanding of the transcendent is an uneducated one … I think you need to spend time with real scientists who gaze at wondrous things every day.”

Our modern Gnostics do love to “educate” us until we see things their way, don’t they? I must plead guilty to the charge of ignorance; there are vast swaths of knowledge I do not possess, vast expanses of information and experience of which I know little. I have far more questions than answers about this life, its origins, and its meaning. And I find myself entirely comfortable — excited, even — in this very uncertainty.

But as far as “gazing at wondrous things,” well, let’s see: in my profession, I have viewed images generated by flipping nuclear protons in high-power magnetic fields, revealing extraordinary details of human anatomy and pathology. I have marveled at the complex interaction of pharmacological chemicals with cellular physiology, as medications interact with human illness to provide relief and cure. I have sat and listened to the agony of a wife whose husband has Alzheimer’s, who has shared her agony of losing her partner of 60 years, her exhaustion at his care, her frustration with his bizarre behavior, yet heard her irrational but inspirational love and devotion to the man whose life she has shared. I have restored a man’s lost fertility, whose youngest child died at 3 months of age from SIDS — one month after his vasectomy — operating on structures the size of the human hair, using sutures invisible to the eye.

I have sat in utter frustration as every treatment and medication, the very best science has to offer, has failed to stem the progression of aggressive bladder cancer as I watch, helplessly, the agonizing hourglass of imminent cancer spread and ultimate death. I have marveled at the irreducible complexity of the human cell, at the infinite number of variables that influence medical treatment, response to surgery or therapy, and clinical outcomes; I have carefully dissected, removed, and cured an aggressive cancer of the prostate while watching another whose treatment failed die slowly and painfully from the same disease. I have seen men die both with and without God — seen the peace and serenity in the eyes of one, despite almost unbearable agony, and the hopelessness and terror in the eyes of others with no such hope. I watch and participate daily in the complexity of life and death, health and disease, the richness of human experience, and the miracles of science applied to improving lives. I live daily with body, with soul, and with spirit — and engage each in its place. I find all these things rather wondrous, humbling, and, yes, transcendent — silly me.

But perhaps my esteemed skeptical scientist is correct: maybe I should hang out with “real scientists” who peer through telescopes and, with tunnel vision, star-gaze their way to meaning and purpose in cosmic clouds and multiple universes, caressing their theoretical physics in orgasmic intellectual onanism. Perhaps then I will learn the real meaning of life, thereby discovering their secret to transcendence without God, with mysteries hidden deep within their superstrings, antimatter, and quarks. That such things are fascinating is doubtless true; that they may be true is doubtless fascinating; that they seek to explain why we love, or sentient, or hateful, or evil — and to what purpose we exist in space and time — is both futile and fascinating.

Or perhaps instead, I will remain at the vortex of a unified field of Truth, with God, both sovereign and merciful, at its center, immense as the cosmos and intimate as the heart. From where I stand, the universe, and my place in it, look quite wondrous indeed.