Spinning Beginning: The Cable Spinning Process

Previous posts in the New Narrows Bridge Series:

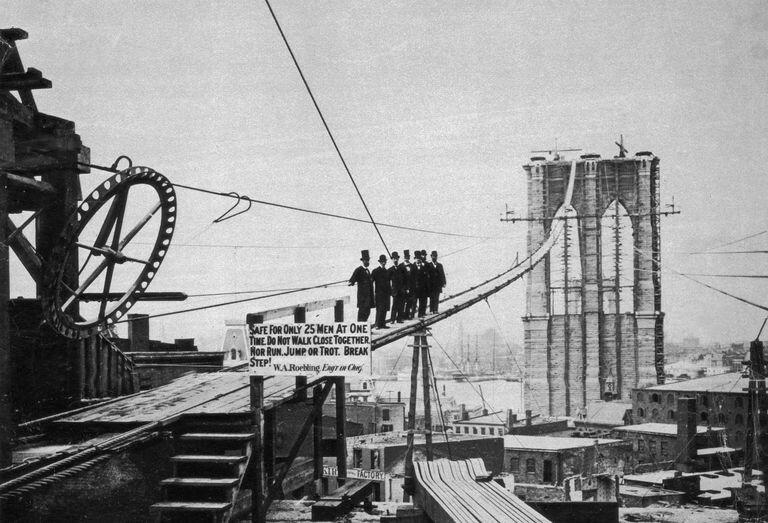

Cable spinning is not a new technology. First used in the mid-1800’s, its most noteworthy early application was the Brooklyn Bridge—the first suspension bridge to use steel, rather than iron, cables. Its designer — generally considered to be the father of modern suspension bridge technology — was John Roebling, a German immigrant who leveraged his knowledge of bridge building into a notable and influential career in bridge design. Ironically, the steel cables produced by Roeblings’ company were instrumental in defeating German U-boat threats in the North Sea in WW I.

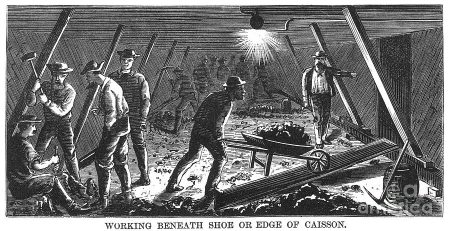

Bridges had been suspended from iron chains for nearly 2000 years. But the idea of spinning a wire cable right in place over a river — adding a few strands with each pass — was both new and very radical in the nineteenth century. In 1841, Roebling — a wire cable manufacturer — wrote an article on constructing bridges by building up large cables from many smaller wires, borrowing and enhancing some earlier ideas from European engineers. He first built such a suspension bridge over the Allegheny River, and subsequently completed a series of bridges, including one which spanned the Delaware River between New York and Pennsylvania, part of the Delaware-Hudson canal system. It opened in 1847, 36 years before the Brooklyn Bridge. Roebling also designed and built the more famous Cincinatti Suspension Bridge, which shows many of the design features used in the subsequent Brooklyn Bridge.

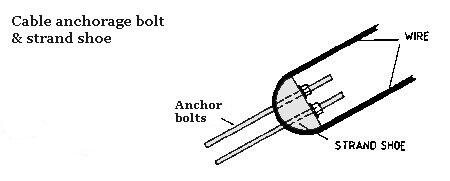

Thin steel wires — 0.5 cm in diameter in the case of the Narrows bridge — are laid down in pairs by means of a traveling wheel (called a traveler or a sheave). Each pair of wires forms a continuous loop, wrapped about a semicircular grooved shoe (called a strand shoe) at the opposing anchorage, which also serves to adjust their tension.

Repeated strands of wire are looped back and forth across the river, then wrapped into groupings known as strands or tendons. When multiple such tendons had been created, they are again bundled together by wrapping, to form the final cable.

Each tendon forms a hexagonal shape initially as wires are laid circumferentially in pairs. Wrapping them compresses the individual wires into a more circular shape. The tendons are well-seen in this recent photograph on the left from the Carquinez bridge construction across the Sacramento River near San Francisco.

Steel cable, imported from Japan, arrives in relatively small spools, each containing about 4 miles of wire (seen in the warehouse, photo courtesy of the News Tribune), are rewound onto larger spools on site on larger drums, 7-1/2 feet tall, containing about 24 miles of wire. The wire ends are connected with steel ferrules, creating a single continuous wire on each drum.

The drums are then transported to the area just behind the east anchorage, where an elaborate, Rube Goldberg set of pulleys and tensioning wheels is used to guide and control the spooling and feeding of the wires.

Note: Regarding the photography: while many of these photos (especially the tour) were taken by me, I am indebted as well to two excellent sources for photographs of the Narrows Bridge construction: The Washington State Department of Transportation site, and the Tacoma News Tribune, which has been running a series on the construction. I should be a bit more specific with photo attribution, but life and time are short — so sue me.

The WSDOT photos, taken by the construction crews, are typically time and date stamped in red in the lower right. And contrary to rumors, I did not take the photos of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge — I was a mere boy back then…

Next: Spinning the Cables